Text im digitalen Raum hat eine bestimmte Materialität. Er ist responsiv und reagiert auf Darstellungsform und Bildschirmgröße. Digitalen Text kann man klicken, scrollen, anfassen. Die User*in kann ihn beeinflussen, kommentieren oder sogar mitschreiben.

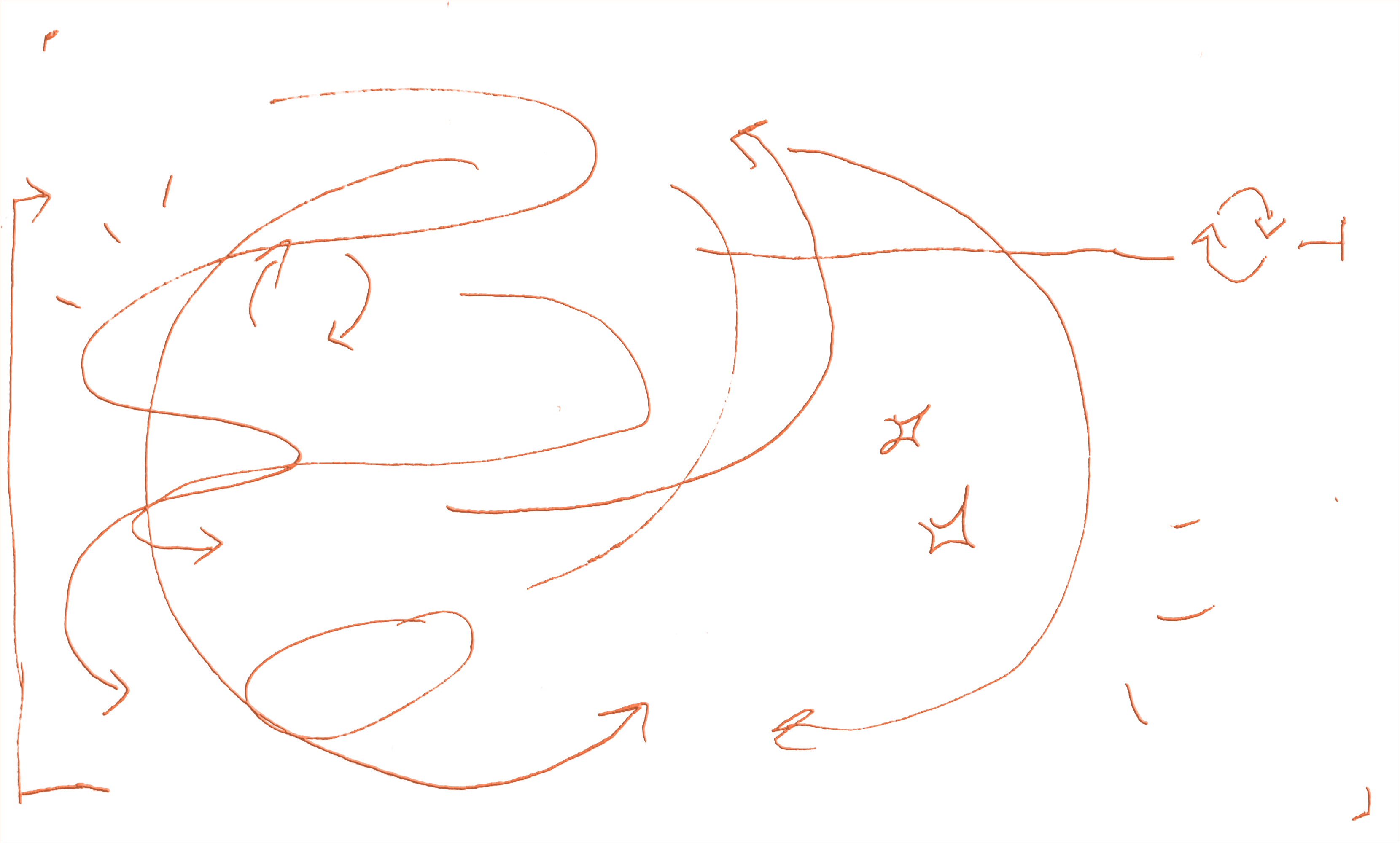

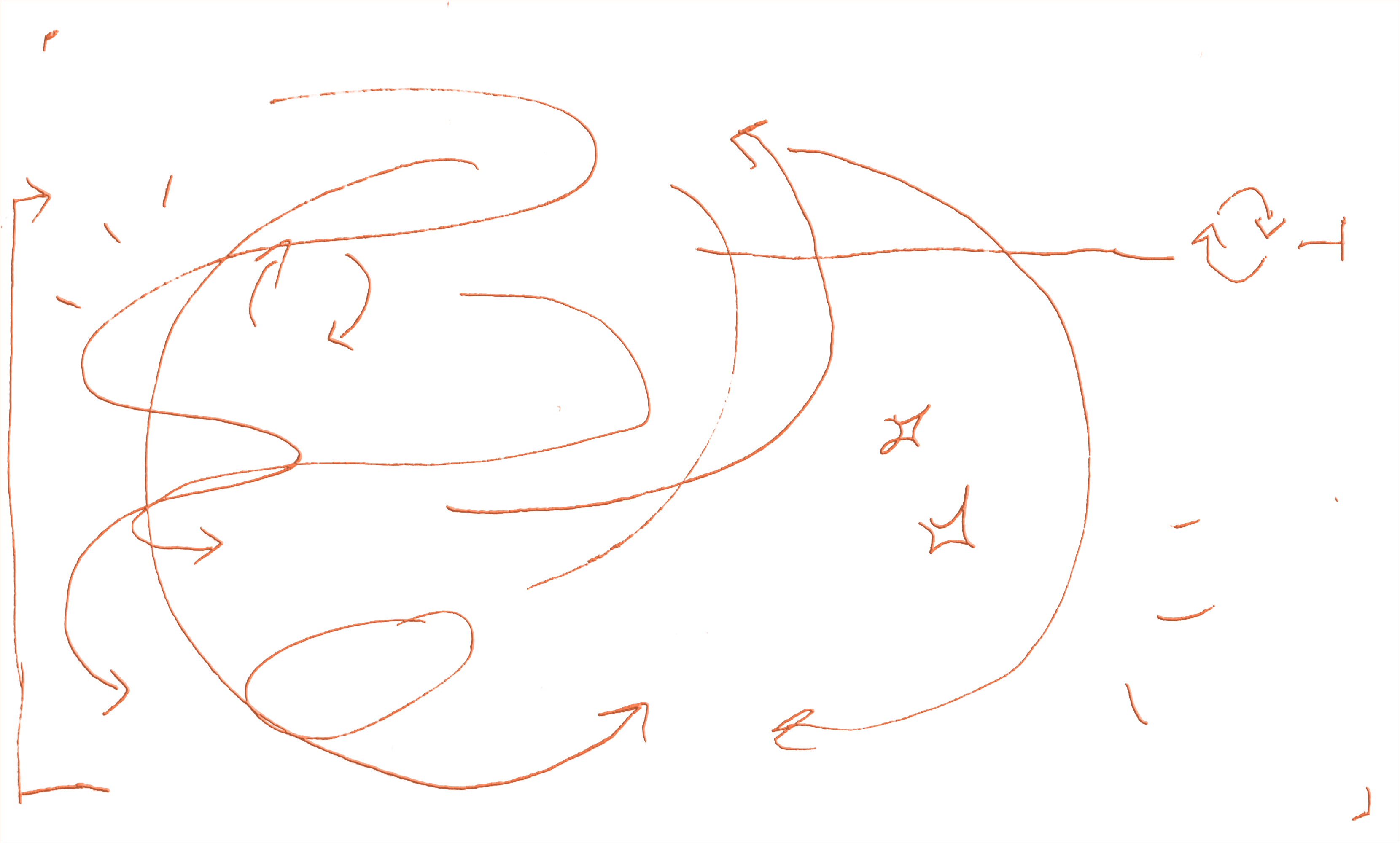

Wie gestaltet man einen solchen Text? Welche Lese-Interaktionen sind im Web möglich? Was bedeutet das für die Rolle der Leser*in bzw. User*in? Diese und weitere Fragen werden wir in dem Workshop untersuchen, indem wir selbst Interaktionskonzepte ausgehend vom Textinhalt erarbeiten.

Entwickle ein digitale Interaktionskonzept für einen Text.

Historically, there is precedence for this shifting role of the reader. Hypertext is not the first textual innovation to do so. Ilana Snyder reminds us that in manuscript days scribes often altered the work they were copying. This blurred, even then, the boundaries between author and reader. Snyder adds that the tradition of print literacy privileges the author. Nothing, supposedly, can be changed about a text once the author (along with the publisher and editor) have finished with it. But French literary critic Roland Barthes, in his interesting essay “The Death of the Author,” points out that a piece of text is “not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the message of the Author-God), but a multidimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash” (116).

Most hypertext theorists would agree. Snyder also points out that oral texts had many of the features that theorists claim are inherent in hypertexts. Oral texts could be revised at will by the speaker, who altered stories depending on the prompts from an audience. But book technology provided a new framing device for narrative and other forms. Murray points out that with electronic text the “author” is procedural, like a choreographer, “who supplies the rhythms, the context, and the set of steps that will be performed” (153). The reader, or as she calls him or her, the “interactor,” is a

“navigator, protagonist, explorer, or builder, [who] makes use of [a] repertoire of possible steps and rhythms to improvise a particular dance among the many, many possible dances the author has enabled. We could perhaps say that the interactor is the author of a particular performance within an electronic story system, or the architect of a particular part of the virtual world, but we must distinguish this derivative authorship from the original authorship of the system itself. (153)”In this sense, Murray is reminding us that each time readers enter a hypertext Web they create a “new” text, written by the choices they make as they travel through the Web. And Landow consistently reminds us that the text an interactor reads is not necessarily the text an author planned. This is an important concept for student readers and writers because it reinforces the fact that readers and writers approach their tasks with purpose, and those purposes may not be the same. All this seems much like the ancient storyteller, who changes the text to fit the wishes of each audience. The audience and the storyteller (author) collaborate to create the narrative.

Nancy G. Patterson, Hypertext and the Reader’s Roles, 2000, pp. 78Today’s internet is bland. Everything looks the same: generic fonts, no layouts to speak of, interchangeable pages, and an absence of expressive visual language. […] Every page consists of containers in containers in containers; sometimes text, sometimes images. Nothing is truly designed, it’s simply assumed.

Ironically, today’s web technologies have enormous design capabilities. We have the capability to implement almost every conceivable idea and layout. We can create radical, surprising, and evocative websites. We can combine experimental typography with generative images and interactive experiences. And yet, even websites for designers are based on containers in containers in containers. The most popular portals for creatives on the web — Dribbble and Behance — are so fundamentally boring they’re basically interchangeable.

How did this happen?

[...]

Treat the browser as a blank canvas and create expressive, imaginative visual experiences. Use the technological potential of current web technologies as a channel for your creativity. Do not be constrained by questions of usability, legibility, and flexibility. Have an attitude. Disregard Erwartungskonformität.

Why Do All Websites Look the Same? – Boris MüllerErwartungskonformität (von lateinisch conformitas “Gleichartigkeit”) bezeichnet eine angepasste Informationsdarstellung eines Systems für einen Benutzer, die einheitlich ist und den Erwartungen des Benutzers bzw. den allgemeinen Konventionen entspricht. Anwendungen sind erwartungskonform, wenn sie nach einem einheitlichen Prinzip bedienbar, die Bearbeitungszeiten vorhersehbar, sowie in der Orientierung einheitlich gestaltet sind. Erwartungskonformität ist laut ISO 9241-110 ein Kriterium der Software-Ergonomie.

Wikipedia